Interview with Ann Marie Ackerman, author of Death of an Assassin

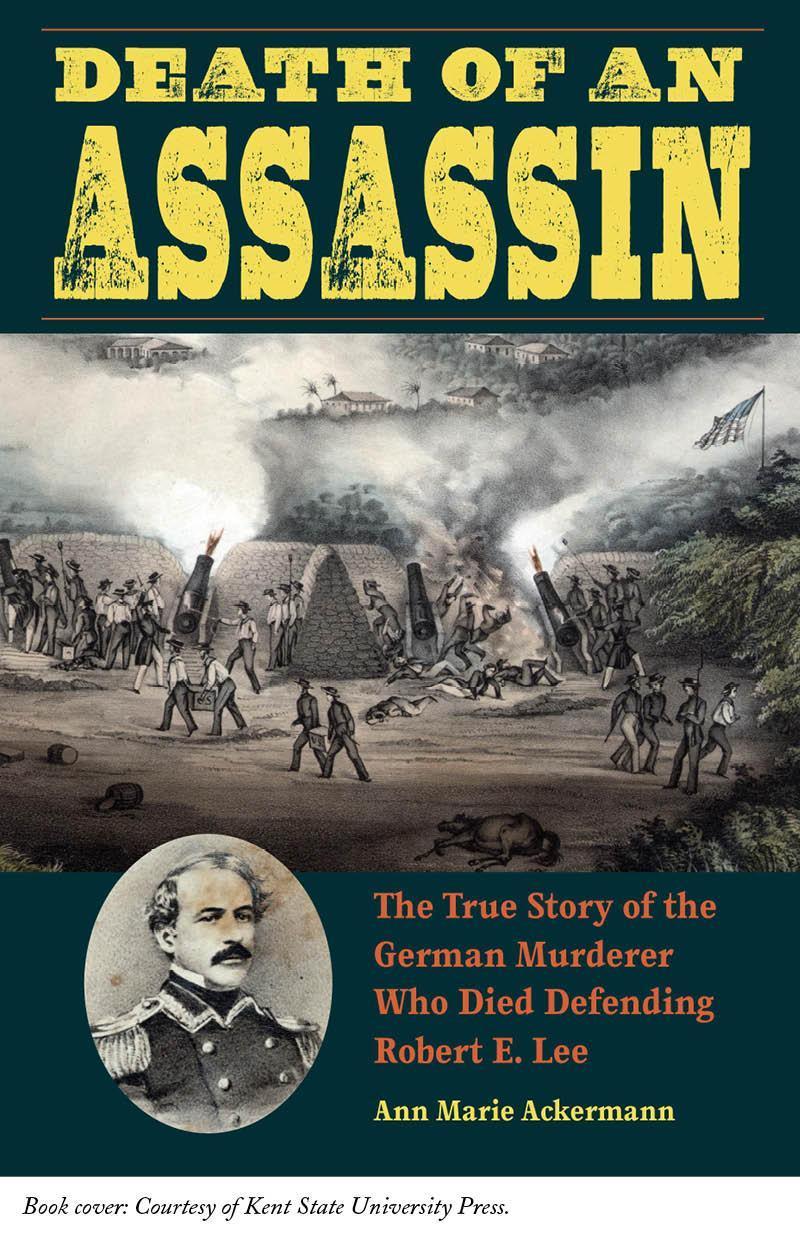

CP: Congratulations on the release of “Death of an Assassin: The True Story of the German Murderer Who Died Defending Robert E. Lee” (Sept 1. 2017, Kent State University Press). This fascinating story would have been entirely lost to time if you hadn’t put together these German and American puzzle pieces — congratulations! Tell us a bit about the mystery you solved:

AMA: Thank you, Carolyn! Actually, it was two mysteries, one on each continent.

In Germany it had to do with its coldest murder case ever solved in the 19th century. An unknown assassin gunned down the mayor of Bönnigheim in 1835, and a tip from American solved the case in 1872!

In America it had to do with a letter Robert E. Lee wrote after his first battle, at the Siege of Veracruz in the Mexican-American War. In that letter, he deified a soldier who died defending him. But that soldier has never been identified until now.

Who would have thought the German assassin and Lee’s hero were one and the same?

CP: As a lover of old handwriting, I was particularly intrigued to hear you used old, handwritten documents to solve this 170-year-old mystery. Tell me more about these documents.

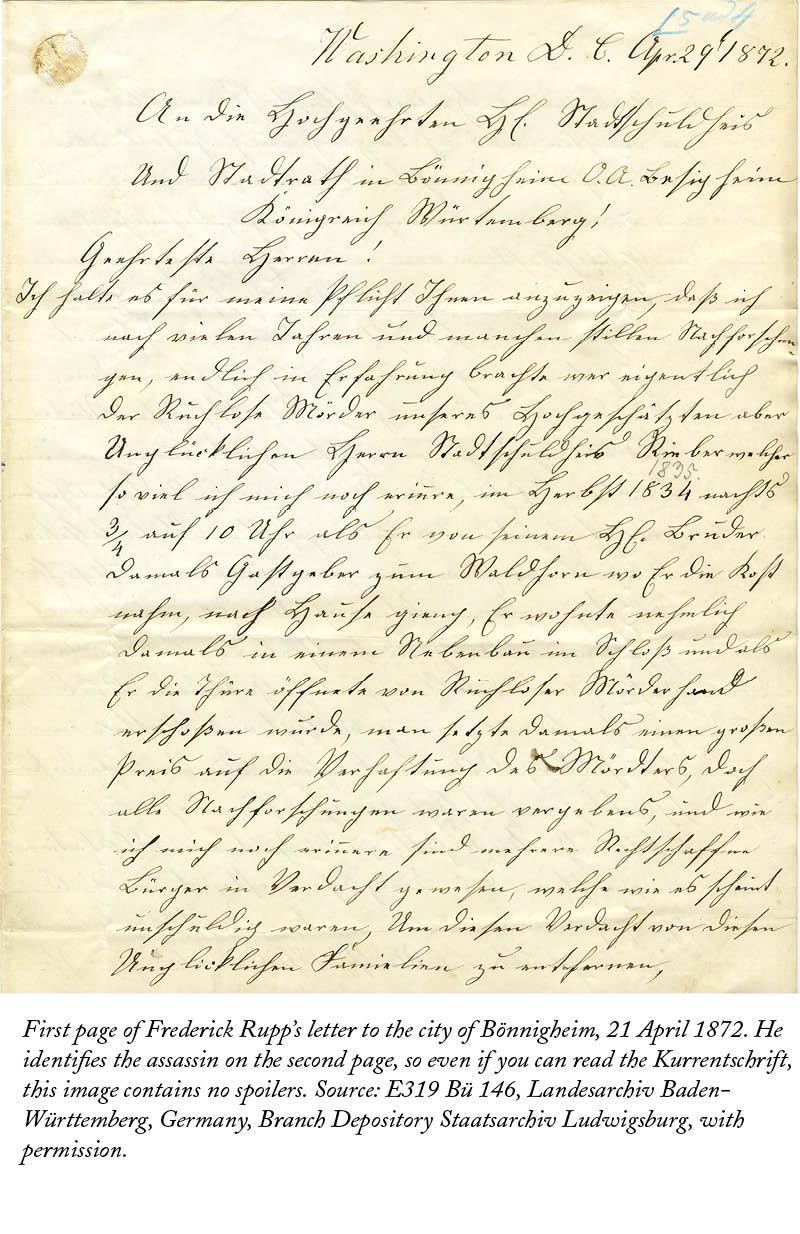

AMA: Germany’s 1835 criminal investigation files were integral to my research. They’re housed in the Baden-Württemberg state archives in Ludwigsburg and are in remarkably good condition. Yes, the paper has yellowed, but the ink is still easy to read. It consists of correspondence, the investigator’s notes to the file, and a protocol book in which a scribe transcribed the witness interrogations.

Lee’s letter is housed in the Virginia Historical Society. I haven’t handled it personally – I worked with digital images instead. The letter is in a collection of papers that were in private possession until 1981. You can see those years outside a professional archive did damage. They hadn’t been preserved as well as the documents in German archives, which are kept in a climate-controlled room. The ink on Lee’s other letters from Veracruz is faded and can be hard to read. And the paper has become brittle and sections of the text in some letters have broken off. Thankfully that didn’t happen to the letter about the unknown hero, but it was sad to see these little pieces of history have been lost.

To figure out who Lee’s unknown hero was, I had to compare Lee’s description of his death against the official casualty list for Lee’s battery and primary sources describing those deaths. Those included a newspaper report from an embedded journalist, published memoirs from other soldiers at the battery, as well as unpublished diaries and letters. The latter were housed at the Library of Congress, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and the Pennsylvania State Archives. Brown University has graciously made one of them available in its digital library.

CP: Had you been looking for something else and did you stumble upon this story by accident? Or, were you specifically looking to solve this mystery?

AMA: I stumbled onto the murder case quite by accident in 2013. I live in Germany and had been researching the history of Bönnigheim’s bird life for a historical society publication. The chair of the society gave me the transcript of an unpublished forester’s diary from the 19th century, thinking I could find references to birds there. I was surprised when the forester talked about finding the evidence to corroborate the solution to a 37-year-old murder!

I used to practice criminal law in the United States and it was immediately clear to me how unusual this case was. Before the advent of DNA and modern forensic techniques, a time span like that was unheard of. And in fact, this case turned out to be a German record breaker. I thought I had a good story for the Germans.

That drove me to the German archives to research the case. I simultaneously began tracking the murderer, who had fled to the U.S. to escape justice, through the American archives. My biggest surprise was discovering Lee had written a letter about him. Suddenly I released this story would interest American readers too.

CP: How is 19th-century German handwriting different than contemporary handwriting and what were some particular challenges of reading old German script? If you couldn’t read it, what resources did you rely on to decipher the old writing?

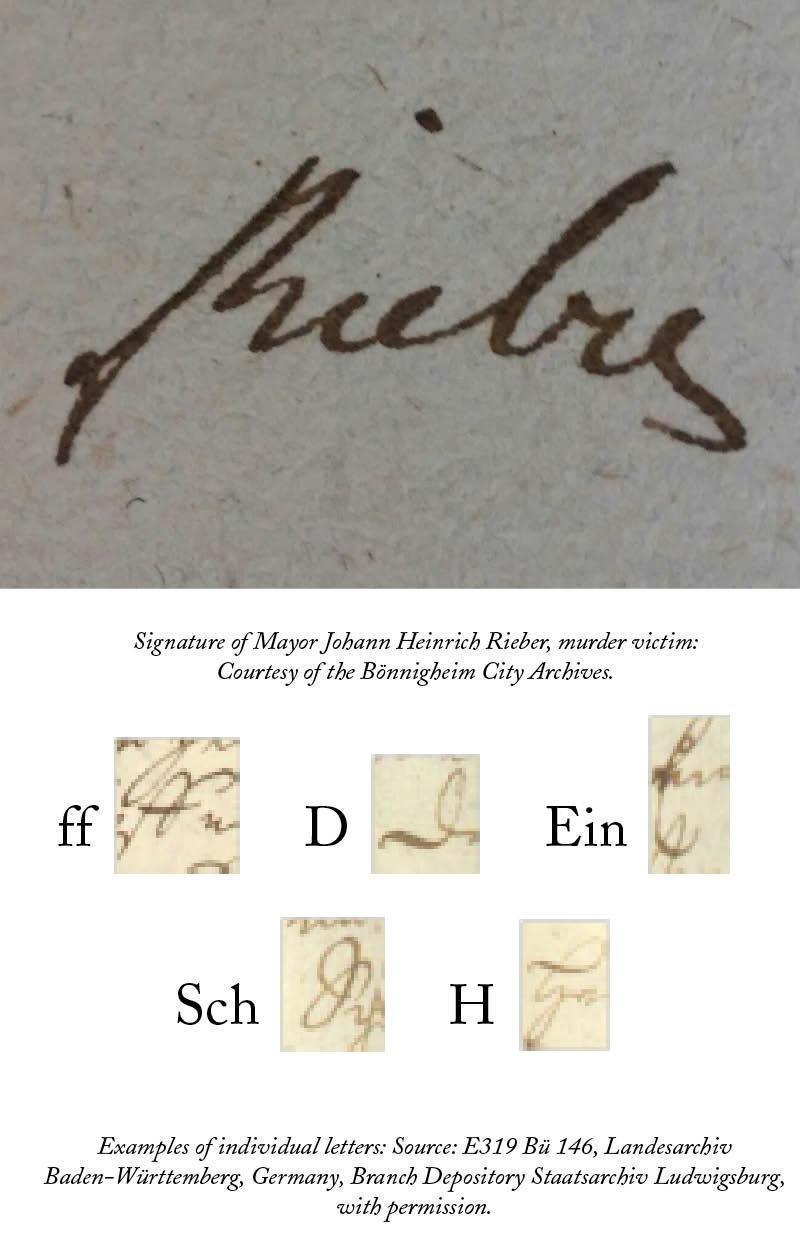

AMA: The 19th-century Kurrentschrift is different enough that a modern German wouldn’t be able to read it without practice. Many letters look completely different. I taught myself how to read it with the help of a workbook, an adult education course, lots of practice, and tips from helpful archivists.

But not everyone’s handwriting is the same. A scribe recorded the investigator’s interrogation of the witnesses and always wrote with clear, precise handwriting. But correspondence in the file didn’t always showcase exemplary script. For instance, a letter a surgeon wrote summarizing the autopsy findings was hard for me to read. I’m lucky to have a physician friend who can read the Kurrent handwriting and was probably even better than an archivist at teasing out the medical terms. She even caught a medical mistake the scribe made while recording the autopsy.

After the handwriting, the language was my second biggest obstacle. German is my second language and that always worked to my disadvantage. It took me longer to tease out the text. Terminology has changed. But if I got stuck, the archivists were always willing to assist me. They deserve a thousand salutes for their professionalism and helpfulness.

CP: I agree! Did you discover any particularly amazing old phrases, words or idioms not used in modern language?

AMA: Obviously, the language has evolved over the past 180 years. Letter writers used different salutations back then than they do today. And in some cases, the words have changed. For instance, a modern German would say “laufen” for “to run,” but in the investigative file, all the witnesses said “springen,” which today would mean “to jump.” You get a feel for what was meant by reading a lot of material, not unlike how a child acquires language through exposure.

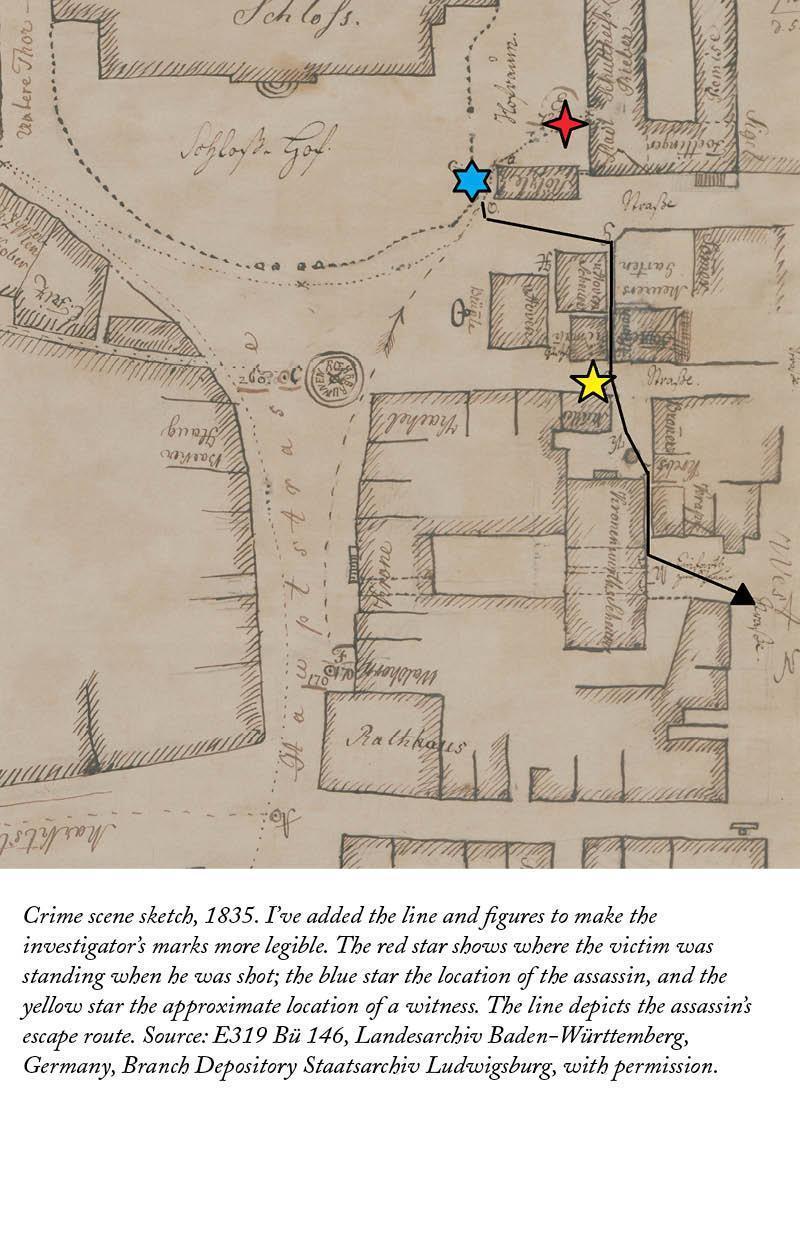

One of the most delightful things I found was not a text, but the 182-year-old crime scene sketch. There’s a lot of history recorded in this image alone. It also contains examples of the Kurrentschrift. The word just to the left of the blue star, for instance, is Schloß-Hof, or “palace courtyard.”

CP: You run a historical true crime blog; what about this genre is particularly appealing to you? Have you used old handwritten letters/documents to solve other mysteries?

AMA: I have a background in criminal law, so that made this genre especially interesting to me. The Robert E. Lee letter is part of my book, and it was interesting to read Lee’s handwriting as well. It’s also antiquated, but much easier to read for me as an American than the old German handwriting.

No, I haven’t solved any other mysteries through old, handwritten documents. A record-breaking international cold case with a connection to an American Civil War hero will come along only once in my life. But I’m open, if you’ve got a mystery!

There are some other great historical true crime books out there based on archival research in Europe. Douglas Starr’s Killer of Little Shepherds documents the evolution of forensic science against the backdrop of the 19th-century investigation into France’s version of Jack the Ripper. Holly Tucker’s City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and the First Police Chief of Paris chronicles a 17th-century investigation into a huge French poisoning ring that reached the court of Louis XIV. Both did extensive research in the French archives

CP: Your blog has entries on Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, Robert E. Lee and Mark Twain. Is the 19th century a time frame that particularly intrigues you?

AMA: I like the Civil War and adore Mark Twain, so yes. But there’s a more pragmatic reason for sticking to the 19th century, at least in Germany. Once you go back to the 18th century and earlier, you encounter more and more Latin. It was the lingua franca. I had Latin in high school and college but can’t read it any more. So I have to stick to the 19th century if I want to do research here.

CP: I understand you will be traveling to the US for the book tour. Where can people see you?

AMA: I’ll be in Tennesse, Indiana, Wisconsin, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Check my website for a more precise list of events.

CP: Thanks! And again, congratulations!