Marcel’s letters are back in France

One of the unanticipated delights of having a book out in the world is hearing from readers. Every few months I’ll get an email or handwritten note. Most times, people want to tell me about their reading experience. Sometimes they have a question or two. Occasionally they have a complaint. And sometimes they want to share an extraordinary connection, such as the time I heard from a woman whose mother-in-law knew Marcel.

18 months ago, in February 2024, I received an email from a reader named Trudy. Her note began like many others, then transitioned to her core question: what was the plan for the safekeeping of Marcel’s original letters?

I’m used to that question. I’ve met with 70 book clubs, and the question of where the letters were has come up nearly every time. I’d tell people the letters were still in my safe deposit box. I’d usually add a comment about how that was not where they should be, but for the time being, the letters were safe and secure.

Trudy’s email went on to tell me that she was an archivist, and offered help — for free, she noted — should I want help finding an institution to send them to.

On the surface, her offer seemed lovely. But over the years, in addition to feeling delight from hearing from readers, I’ve learned to be skeptical of their claims. I’ve received emails from people claiming to be, or have, all sorts of things. So, I read Trudy’s offer with skepticism.

Until I Googled her.

Trudy Huskamp Peterson is not just an archivist. For decades she worked at the National Archives in Washington, DC, and she served as the director of archives and records management for the United Nations. Let me repeat that: she was director of archives for the United Nations. She served as president of the Society of American Archivists, and was the first woman to hold the position of Archivist of the United States. Did you know there was an official Archivist of the United States? Me neither.

Trudy is, to put it mildly, a big deal. Similar to the way the Universe seemed to bring people like Dixie, Louise, Wolfgang and others into this project’s orbit, I wondered if the Universe had somehow pulled Trudy in, too.

For a reason I still don’t understand, my emails to Trudy would never go through to her. She could email me, but I could not email her back. So I corresponded the old-fashioned way: through written mail. I told her that more than a decade ago I reached out to the French National Archives and another WWII museum in Paris (see page 316 of Marcel’s Letters) to inquire whether they might be interested in providing a permanent home for these letters. After months of waiting for responses that never came, I resigned myself to their disinterest. After that, I’ll be honest that finding a home for the letters fell off the top of my to-do list. Life happened. The letters remained at my bank. I knew they were safe. Marcel’s family knew they were safe. I wasn’t going to sell them on eBay or something. But the long-term care of the letters remained a loose end. I told Trudy about my hopes for their long-term protection, and conditions I had for any potential donation. Conditions included permanent physical protection of the originals, accessibility to the originals by his family members, and that the contents of his letters would be made available to those researching the experiences of WWII French forced laborers and Service du Travail Obligatoire. Marcel’s testimony of life inside a labor camp deserved these protections.

Trudy reached out to her network of archivists in France, and provided a short list of relevant institutions that might be considered. The short list included the Eure-et-Loir Department Archives in Chartres, and the Seine St. Denis Department Archives in the Île-de-France region. The first archive is near Berchères-la-Maingot, the rural village where Renee and the girls lived during the war. The second archive covered Montreuil, the city within greater Paris where the family lived before and after the war.

I composed letters to the archives. I heard back from one almost immediately, and the other archive a couple of months later. Both were interested and addressed all concerns that Marcel’s letters would be permanently cared for.

In the end, the Eure-et-Loir Archives in Chartres felt like the right home. If you walked a short distance down the road from Marcel and Renee’s land on the edge of Berchères-la-Maingot, you could look due south and see the distant spires of the Chartres Cathedral (see page 309 of Marcel’s Letters). The Archive is about a half mile from those spires. Sending them to Chartres felt like these letters were returning to their intended destination. Or, close, anyway.

The next big step was to share the plan with Marcel’s family. The slowness of the process meant I had time to prepare to let these letters go. 98% of me was absolutely sure this was the right decision. 2% of me was sad at the permanence of the act. I’ve had custody of the first five letters for nearly 24 years. We’ve taken quite a journey together. But I’ve also long known my safe deposit box is not where these incredible letters should be. My tenure as caretaker was not permanent.

By early August everything was in place to finalize the donation. I spent two weekends gathering documentation on Marcel, and I created a braided timeline of French forced labor combined with dates of his letters. I outlined the dates Marcel had been in Spandau Prison, cross-referencing information provided by the Daimler archives in Stuttgart and the Arolsen Archives–International Center on Nazi Persecution in Bad Arolsen. I made note of significant passages in select letters. I signed multiple copies of the donation contract, and prepared a thumb drive with scans and documents.

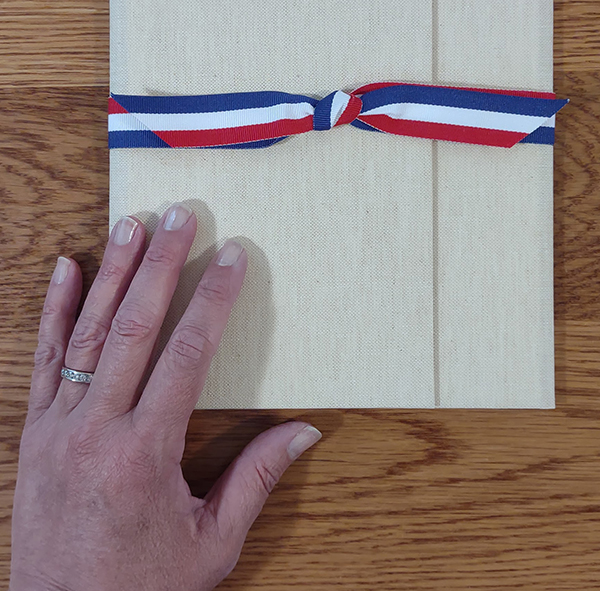

On pages 187–188 and 239–241 of Marcel’s Letters, I wrote about a custom linen-wrapped portfolio I had commissioned in 2012. After it became clear returning the original letters to the family was problematic, the portfolio went onto my office bookshelf, where it remained for more than a decade, pressed flat between two hardcover books on typography. It was finally — finally! — time to use it.

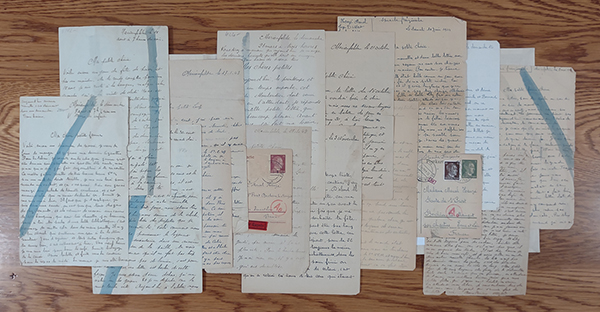

On Saturday, August 16, I retrieved the letters from my safe deposit box. For as intimately as I knew the handwriting on these pages, they still held surprises. It had been years since I held them; I had forgotten how soft the paper felt. I had forgotten how intense the blue and red of the chemical censor marks were. Once back home, I took a few photos, then the letters went into the portfolio, which was tied shut with a red, white, and blue ribbon.

On Monday, August 18, I took the box to FedEx. During the days that followed, I tracked the shipment. I received an email noting it was held up in customs, and wondered if it had been opened and inspected. I wasn’t surprised at the possibility of that happening, though I fretted about the letter with the hand-drawn backward swastika. Was there some regulation somewhere that made transporting artifacts with a swastika a problem? I wasn’t sure. I hoped the documentation showing it was headed to an Archive would provide a pass.

Nine days after I dropped the package at FedEx I received an email from my contact at the Eure-et-Loir Archives assuring me the package arrived in perfect condition. He provided a newly assigned catalog reference number for the letters, and what felt like a sincere thank you.

After more than a year of working on this donation, it happened without fanfare. Entry into the Eure-et-Loir Archive was quiet, confirmed by a simple email. But it felt like a big day. 82 years after the letters were written, the pages were finally back where they belong: in France, just 12 kilometers from their original destination. This time, though, their future was safe and secure.