My Summer of Demolition and Renovation: Remodeling Our Bathroom and Learning I Had Cancer in My Face

An Essay

Twenty-four years ago Aaron and I purchased the home where we still live. It’s a classic mid-century rambler with three small bedrooms and a full basement. Sometime in the 1980s, a previous owner converted the one-car attached garage into a large kitchen, and the oversize lot had big, magnificent trees. As the saying goes, it had good bones.

As with any 70-year-old home, things need fixing and updating, and we’ve tried to tackle one project a year. Years when money or time was thin, we’d do something small like update a light fixture. Other years projects were bigger. One year we painted the exterior of the house. Other years we hired people to replace flooring, windows, the roof (twice), and we added a bedroom and bathroom in the basement.

But there was one project we never had the gumption to tackle: the main-floor bathroom.

The room had issues. It didn’t have usable electrical outlets, and the light switch was in the hall. We tried to remember to tell guests where to find the lightswitch, though we presume somewhere along the line someone has had to go potty in the dark because they couldn’t figure out how to turn the light on.

Over the years the bathroom’s original linoleum floor tiles started to crack. A hole in the floor near the tub turned black. The tub leaked. Still, we put it off. To fix it right we presumed we’d have to take the room down to the stud walls, and the disruption seemed overwhelming. So did the price tag. One potential contractor told us projects like ours started at $75,000.

———

In the fall of 2023, Aaron and I decided the bathroom had to be addressed. I reached out to a local kitchen and bath remodeler, Preferred Kitchens. Neither Aaron nor I wanted to spend $75k, yet neither of us had the interest or expertise to do it ourselves. We could do some things: demo, painting, hooking up a new faucet. But we didn’t know any tradesmen. When it came to a tiler, electrician, or carpenter, we’d be at the mercy of Google and we weren’t comfortable with that. We wanted to work with someone who had connections and expertise.

The first planning meeting with Preferred Kitchens was in December, 2023. Aaron and I were told what we hoped to hear: they’d help select materials, order all the pieces and parts, then coordinate vetted craftsmen to provide top-quality work.

I came to that meeting with a preliminary sketch, colors, and ideas. I hoped to be the client I wanted my clients to be: clear in vision, collaborative, decisive. Some of my initial ideas had to be abandoned due to cost, but our designer and project manager, Jaime, brought new options and ideas to the table. As suspected, the room would have to be taken down to the stud walls in order to update the original wiring.

Three months later, in February 2024, Jaime and I had a third and final planning meeting. We reviewed detailed schematics and all material selections. The new bathroom would have small hexagon marble floor tiles, a dark blue vanity, a new oak linen cabinet, stone counter top, Kohler tub/toilet/sink, a fancy new light fixture, and … drumroll … electrical outlets. I handed over a deposit check. The remodel wasn’t $75,000, though it would cost half that.

COVID-era supply chain issues had mostly abated, but Jaime expected it might take two months before all parts were delivered. She said her team would put together a project schedule once they had confidence on timing. Weeks later, Jaime emailed the schedule. Demo was scheduled for May 15. After that, the carpenter would shore up flooring, then the plumber and electrician would do their work. She allocated a week for drywall and two days to tile the floor. The room would be painted, the carpenter would install the vanity and linen cabinet, then the stone vendor would come out to measure the counter top. Finally, the counter and sink would go in, and the carpenter would finish the trim work.

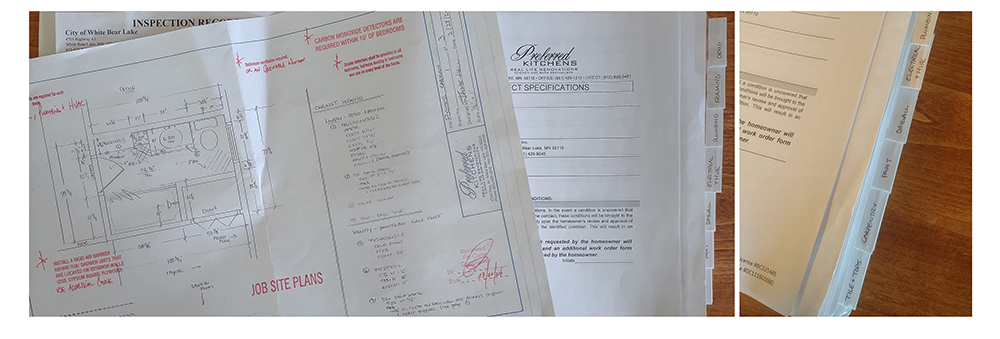

I was elated to have a solid plan. Jaime assembled a three-ring binder for our project. Every detail — down to the placement of the knobs on the vanity — was carefully documented. Each tradesman could consult his section in the binder to see a list of tasks, supplies, and schematics.

My OCD graphic designer heart was thrilled.

———

On a Tuesday morning in mid-April, one month before demo was schedule to take place, I called to make a dermatology appointment. Similar to changing a furnace filter or cleaning out gutters, it was routine “maintenance.” Also similar to those tasks, it was a to-do that had been easy to fall behind on. The receptionist looked up my medical record and noted it had been more than five years since I had been seen, which meant I was considered a “new” patient. She told me they weren’t scheduling appointments for new patients until February — of 2025.

“Unless,” she added, “you could come in today at 1:00.” She explained they had a cancellation that morning.

“I’ll take it,” I said, feeling lucky.

Three hours later I was sitting on the exam table. The dermatologist I had seen previously was no longer with the practice, so a new doctor was looking me over.

All previous dermatology appointments had been uneventful. Any spot or lump was met with confident assurance that it was a dermatofibroma or a senile purpura — a.k.a., nothing to worry about. One dime-size spot on my breast had been assessed by my previous dermatologist; she assured me it was a benign seborrheic keratosis. If I ever wanted, she said, I could have it removed.

Over the previous year or so the spot on my breast had changed enough that I wanted to have it looked at and, as she had suggested, have it removed. I showed the new dermatologist the dime-size spot and pointed out a few other spots and bumps: one on my left ankle, another on my right shin, a dry spot on my abdomen, and a small bump at the base of my left nostril. I wasn’t particularly concerned about the bump below my nose. It wasn’t discolored. It didn’t have an irregular edge. It didn’t bleed. It didn’t have any of the characteristics we’re told to watch for. I explained it was like a zit that never turned into a zit. I had recently seen a photo of myself where the spot seemed more noticeable than usual and when we discussed removing the spot on my breast I asked if the spot under my nose could be removed, too.

The dermatologist looked at it through her hand-held scope and said she was “55% sure” it was nothing to worry about. She said it would be easy to remove and offered to remove both spots right then and there.

The following afternoon I was scheduled to review graphic design student portfolios at UW-Stout. I was vain enough not to want to sit across from students with a Band-Aid below my nose, so we scheduled the appointment for the following week. The appointment lasted all of 10 minutes. After numbing the two areas, the spots were shaved off. I was surprised the tissue from below my nose was put in a specimen vial. The dermatologist had seemed so unconcerned about it. Sending it for analysis was standard procedure, I was told. No one seemed worried.

When I got home I looked at the excision below my nose. I was thrilled. It was so small it didn’t even need a Band-Aid. It seemed small enough it might heal in days. And it did. By Friday morning it was barely visible.

———

Carolyn & Aaron, October 2023, six months before biopsy

———

Shortly after 5:00 on Friday, April 26, I received an email saying biopsy results were available. I logged in to the secure online health care portal.

The dime-size spot removed from my breast was, as expected, benign.

The small spot below my nose?

Basal cell carcinoma. I had to Google it.

A sidenote to healthcare companies: it doesn’t make for a fun weekend to send test results showing cancer on Friday after close of business.

The dermatologist’s office was closed on Monday, but a gentleman called early Tuesday morning. He explained the next step was Mohs surgery, which is where a doctor cuts the cancer away bit by bit until they get clear, cancer-free margins. Because of where the bump had been, they offered the option of plastic/reconstructive surgery.

The words made my blood run cold. It had been such a small spot. The thought of needing plastic/reconstructive surgery seemed so … serious.

Aaron works in surgical services at Regions Hospital and he jumped into action. The next day he approached a plastic surgeon he trusted who specialized in ear/nose/throat cases, and asked if he would do my surgery. He agreed.

By the time I got a call from the surgery scheduler, which didn’t happen for another long, sleepless week, I was able to tell her Dr. Harley Dresner had agreed to do the reconstructive surgery. In the following weeks I would hear nothing but glowing reviews of his work. “If I had to have my face cut open, I’d want Harley to do it,” two different people remarked.

Days later the scheduler called again: Mohs surgery was scheduled for Tuesday, June 18. The plastic/reconstructive surgery with Dr. Dresner was scheduled for the following day.

Aaron and I had several long conversations about what surgery might mean. I tried not to obsess about what ifs, but the possibility of having part of my nose removed kept me awake at night (…for those of you who read Marcel’s Letters you know I’m not a good sleeper to begin with). Losing part of my nose was a legitimate concern. With melanoma — which is a more aggressive cancer than I had, to be clear — Aaron said they often take a one-inch margin to ensure they get all the cancer cells and roots. He didn’t know what the typical margin was with basal cell carcinoma. If they had to take an inch, the entire left side of my nose would be gone. If they took a half inch, I’d lose the nostril and nasal sill. If they took a quarter inch I’d lose part of the nostril and part of the nasal sill. Even if they only took an eighth of an inch, I’d lose something.

But what was the option?

“They’ve got to get that shit out,” Aaron stated one day when I questioned if the surgeon really needed to remove so much. “We’ll deal with whatever’s left.”

It felt easy for him to say. It wasn’t his face.

———

Demolition of our bathroom was scheduled to begin the following week. I reframed the mess they were about to make. To use Aaron’s words, the demo crew would be “getting the shit out” to make space for our beautiful new bathroom. Rather than looking at demolition as an inconvenient mess, I tried viewing it as a fresh first step.

In less than an hour, the three-man demo crew removed the vanity, sink, tub, toilet, linen closet, and linoleum floor. In a handful of more hours the room was down to stud walls.

The three-yard dumpster in front of our house was full. The shit was out.

The next morning the carpenter began shoring up the sub floor. Days later the tub was installed, then drywall went up, then the tile floor went in. The care and craftsmanship that went into the rebuilding felt like a good omen.

———

Only a handful of friends, immediate family, and a few clients knew about my upcoming surgery. I didn’t tell others because I didn’t want to under- or over-theorize what the outcome might be. Aaron reminded me I might not even need reconstructive surgery. Maybe the first round of Mohs would be all they’d need to get it all. Maybe they could whip the spot together with a few stitches.

The short list of people who knew included Jaime. As soon as surgery was scheduled I asked her to block off the week of surgery. I didn’t know what I’d need on the days of, or after, surgery, but in case I needed a quiet house, I didn’t want people coming and going, hammering and sawing. She assured me none of the tradesmen would come to the house that week and modified the schedule accordingly. I was grateful.

In the weeks after the diagnosis, I berated myself for not having scheduled the dermatology appointment sooner. I berated myself for the blistering sunburn I got the summer I was 13; I had recently learned a bad burn before the age of 18 raised my chances for skin cancer. I berated myself for having used a tanning bed in the spring of 1987 before high school prom, and in the spring of 1991 when I was finishing my last semester of college. I berated myself for not having a daily practice of applying sunscreen, and for the various sunburns I had gotten on vacations or when doing yard work. To say I was unkind to myself would be an understatement. During those weeks, one of Aaron’s favorite sayings from his decade working as an ER nurse kept coming to mind: “If you’re gonna be stupid, you gotta be tough.”

I steeled myself to be tough. Cancer seemed an inevitable outcome of my stupidity. Disfigurement seemed like apt punishment.

The hardest part was the unknown. Would I walk out of surgery with a few stitches? Or would I walk out missing part of my nose? One night I went down a rabbit hole of researching silicone prosthetic noses. Helpful tip: Don’t do that.

What I desperately wanted was a Jaime-like three-ring binder with detailed, specific plans for demolition and reconstruction. Instead, I’d meet the doctors moments before the procedures. There would be no advance planning, no reviewing schematics, no making selections. Instead, it felt like I was signing up for one of those home makeover reality shows where you hand over your keys, leave your home for a bit, and cross your fingers that you can live with the end result.

The weekend before surgery I blocked off time each day to do yoga and meditate. I wanted to go into the week with the best possible mindframe. One of the guided meditation sessions, by happenstance, had a theme of forgiveness. The woman leading the session asked us to think of a person we wanted to forgive. With a sweep of uncharacteristic self-grace, I tried to forgive myself for all the cruel things I had said to myself the previous weeks.

Then I cried.

———

Aaron drove to the Mohs surgery appointment. I was anxious, but calm. Maybe I was in a shocked state. I hoped to keep my nose, but if I couldn’t, I wasn’t going to stop the doctor from taking it. More than anything I wanted the procedure to be over to have clarity on what would be left.

After a brief consultation with the surgeon, Dr. Tan, his assistant injected lidocaine into my nose and upper lip, and he removed skin surrounding the site of the original biopsy. The procedure only took minutes. The assistant bandaged my face, then escorted us to a special waiting room. Meanwhile, the specimen was mapped and sent for microscopic examination. Aaron and I were told it would take 60–90 minutes before they’d have results.

I was called back to the exam room in just 45 minutes, so I knew the news wasn’t good. The specimen showed cancer cells along the margin. Dr. Tan needed to remove more.

The front of the nasal sill had been removed during the first round, but that was all he was going to need to take. The cancer was growing in the direction of my lip, not my nose. In that moment I felt one thing: extraordinarily lucky.

The second round of removal didn’t get all the cancer. Nor did the third. By the time the fourth round of removal was completed, an oval of skin that extended half way from my nose to my lip had been removed. Any notion of closing the hole with a few stitches was long gone. In fact, Aaron said Dr. Dresner had a bit of a “meat puzzle” ahead of him.

But by day’s end demo was over. Dr. Tan got the shit out.

———

The next morning Aaron and I headed to Regions Hospital. For fifteen years I had told Aaron that if I ever needed surgery, I refused to have it at Regions. If I had to get naked in front of his co-workers I would never — ever, ever, ever, ever, ever — go to another one of his holiday work parties.

But there I was. Fixing the hole in my face was more important than pride or privacy.

We were escorted to a pre-op room where I changed into a gown. Vital signs were checked. My medical history was reviewed. As Aaron’s co-workers cycled in and out of the room to conduct various pre-surgery checks, Aaron tried not to be “on duty,” but when we were alone he adjusted the tape holding my IV in place, the position of my bed, my pillow.

Fifteen minutes before surgery, Dr. Dresner came in and introduced himself. He took a thin marker and drew on my face to show how he suggested we approach the reconstruction. To get enough skin to close the hole, he needed to cut from the outside of one nostril to the inside of the other, and all the way down to the lip in the shape of a letter ‘V’. The two sides of the ‘V’ would be pulled together to create an ‘I’. Combined with the incisions around the nose, it would create the letter ‘T.’ It was a good way to explain the procedure to a someone who works with type.

A sidenote for the nerdiest of my type nerd friends: The ‘T’ of stitches ended up looking similar to the capital T in the typeface Malliandra Script.

Dr. Dresner asked if the plan sounded ok.

“I trust you,” I said.

What was the option? I knew less about surgery than I knew about tiling or electrical work. I had no basis to counter his approach. I had no option but to trust him.

After completing final paperwork I was wheeled into the operating room.

Renovation was about to begin.

———

Surgery lasted an hour and a half. Or so I was told. As expected, I woke with a ‘T’ of stitches that extended from nostril to nostril and down to my lip.

After a brief stay in a recovery room, I changed back into street clothes. Aaron and I headed home with a supply of Vicodin, antibiotics, and medicated ointment. Once we got home I put ice on my face.

By the next morning the left side of my face had swelled so much the inside of my top lip faced out. I drank a Vicodin-laced iced coffee, pressed a fresh ice pack to my face, then lay on the couch. The house was quiet, and I was grateful Jaime had modified the schedule.

Before Aaron left for work he made a spreadsheet for me to follow with times to take painkillers and antibiotics, and times to apply the ointment. He occasionally texted and called to check in. I told him it was as if I had gotten the most extreme lip filler imaginable — on one side of my mouth. “I do not recommend this esthetician,” I mumbled.

The truth is I was feeling the same thing I felt the day before: lucky. I could not yet picture what my face would look like once the swelling subsided. The swelling was significant enough that it would be days before I even realized that Dr. Dresner had cut down into my lip. It would be another two weeks before I realized my philtrum was no longer centered below my nose. But I felt grateful Dr. Dresner had done the work; it seemed he had done a skilled and careful job.

———

The following Monday the carpenter showed up to re-start work in the bathroom. I wore a surgical mask while he was in our house; he didn’t need to see the stitches or swelling.

Two weeks earlier we discovered the linen cabinet had been ordered with the wrong color finish — a small bump in Jaime’s otherwise airtight plan — and the big task of the day was for the carpenter to install the correct new cabinet. I felt buoyed. My surgery was in the rear-view mirror and all energy going forward — mine, Aaron’s, Jamie’s, the carpenter’s — could be spent rebuilding.

———

———

Twenty-three days after surgery, the last big step in the bathroom project was completed: the countertop was installed and the sink was re-connected. All that was left was a bit of touch-up painting. The project took longer than planned due to an additional hiccup with the counter top; thankfully it was something that could be fixed by shipping the stone back for one modified cut. We were grateful for Jaime’s project management, and the slight delay was less important than having a beautiful end product.

Also, twenty-three days after surgery the bulk of the swelling in my face was gone. What remained was a swollen knot — a knot that would take another five months to resolve. I hoped to regain movement, feeling, and pliability soon. Talking at length was still a challenge and smiling could be painful, but I was no longer having to drink through a straw or cut my food into toddler-size bits. On the days I was frustrated by the slow pace of recovery I tried reminding myself of the lessons from the wrong color cabinet and incorrectly cut countertop: slight delays didn’t matter as long as there was hope for improvement.

It was still unclear what the final “after” would look like: how obvious the missing part of the nose sill would be, how visible the scar between my nose and lip would be, how obvious my repositioned philtrum would be. I was warned it could take a full year for all residual swelling to go away. Dr. Dresner’s office provided contact information for an esthetician who specialized in masking surgical scars. But her office wouldn’t schedule my appointment until six months had passed since surgery, so it wouldn’t happen until December.

Overall I continue to feel lucky. And grateful. Lucky I called for the appointment the day the dermatologist happened to have a cancellation, and lucky the cancer grew the direction it did. I feel grateful for all of Aaron’s support, grateful to work out of home office so I could heal with privacy, grateful to have good health insurance. And grateful that all summer we were surrounded with caring and skilled craftspeople — carpenters of wood and skin alike.

As for the consultation with the esthetician in December?

It turned out it was just in time for the Regions holiday work party.

———